If I think back to my preteens and early teenage years, an overwhelming memory for me is the delight I felt at spending countless hours playing The Sims 2. Sometimes with friends after school making copies of ourselves, or Sims with weird facial features, but mostly the time spent playing this game was by myself. I can clearly remember rushing to do my homework and then afterwards feeling that total freedom of spending the rest of the evening hearing “Sul sul!” and deep diving into a world that was similar, but also very different from mine.

Of course, it was mostly totally weird and that is why The Sims holds such a special place in a lot of our hearts. Cheat codes were my go to (‘motherlode’ anyone?) and my preteen self felt very cheeky seeing my Sims Woohoo (or hilariously in Polish it’s called ‘Bara-bara’). Hours were spent on designing the most window-forward house (I still want to live in a house in the middle of nowhere with huge windows). You also can’t think of The Sims without remembering the glitches or when your Sim could give birth to an alien… Ah what a deliciously odd dream this game is. I just loved being lost in this gaming paradise with what felt like countless possibilities (and expansion packs!) and as a result escaping the world around me.

Even now, gaming is such a comfort to me. As a society we can often look down on it, but like with many things, I think there are so many positives to it too. Nowadays, I don’t instantly go to play The Sims, but instead Stardew Valley. Gaming still helps me with anxiety; Stardew Valley’s repetitive nature of farming and the charming albeit quirky storylines are simply joyous.

Why am I talking about all this as a weaver? Well, in many ways weaving, gaming and programming have a lot in common.

In her novel Thread Ripper, Amalie Smith interweaves her own narrative of creating a digitally woven tapestry with that of Ada Lovelace, a pioneer of computer programming. She says that like programming, in weaving, the weft (the yarn inserted into the piece) is passed over or under the warp (the horizontal threads that form the base of the weaving).

Joseph Marie Jacquard used punched cards to automate the loom in the early 1800s. Those in turn stored textile patterns and did the exact same thing as the weaving methods beforehand. In computing, the same was later done with zeros and ones. The Jacquard loom that I used at university did this to create patterns that I designed in Photoshop.

Amazingly, the Jacquard loom inspired the British mathematician Charles Babbage to design the Analytical Engine, the first punched-card calculator and a precursor to the modern computer (Smith, on Tate website). As a result, Ada Lovelace then understood the potential of the Analytical Engine and she’s widely known as the first computer programmer.

Lovelace said:

“We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.”

Amalie Smith in Thread Ripper says “The loom is ancient technology, possibly the very oldest. Archaeological findings date the loom back to 5000 BC, making it a predecessor to both mathematics and writing… On the loom, the abstract becomes concrete, because a textile is produced, and the concrete abstract, as an image is formed.”

She continues:

“Weavers were the first programmers, and textile the fabric of the digital.”

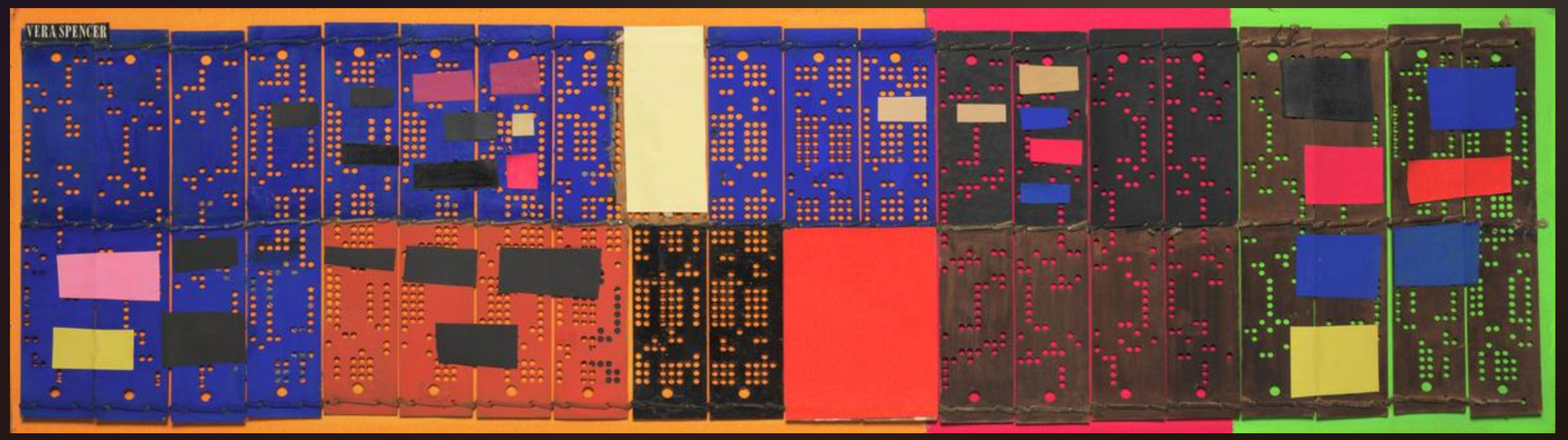

Last weekend, I went to the Tate Modern and saw the Electric Dreams exhibition. By far my favourite piece was Vera Spencer’s Artist versus Machine. She used Jacquard loom punch cards, added background colours and sewed them together. Funnily enough, the author of Thread Ripper, Amalie Smith appears again and writes on the Tate website about Spencer’s punch cards that “by reaching in and grabbing their core tissue, manipulating it, and giving it a new context as an aesthetic material, Spencer fought back against automation with the artist’s means, resisting the digital and insisting on an approach that was in touch with the material world around her.”

This is exactly what interests me about connecting the digital with the material nature of the woven cloth. I’m currently at the start of exploring how to use the digital and make it into something tactile, but at the same time rooting it in a similar background - the usage of ones and zeros, or as a weaver, with the odds and evens of the structure of the loom.

What if I took those memories and snippets that may be so familiar to us who played The Sims, and recreate them on a different kind of computer - the loom? By using an organic material like thread I can make something that resembles a pixelated computer screen. More so, when creating this image, the tool used is in its very nature pixelated itself - the weaving loom; and even more primitive - the backstrap loom.

I’m hoping that through my experiments, I can make something that speaks to our shared digital and humorous memories which we would expect to see on our screens, but instead what if they could be seen on a different kind of 8-bit display; a tapestry.

As always, thanks for reading!

My question to you is: if you played (or still play The Sims), what are your favourite memories of playing the game? Any scenes that particularly stick out? Let me know by replying to this email as I would love to hear them and perhaps include them in some of the work I’ll be making.

Also, don’t forget that I’m holding a few Backstrap Weaving Workshops. Next one is Saturday the 17th of May, more info can be found here. (only 6 spaces left!)

You can find the list at West Dean College here and at Charleston House, here. Would love to see you there.

Have a great rest of your weekend,

Alex x